How I Faced Starvation, Poor Performance and Lost Dreams, Yet I Have Dedicated My Life to the Overweight, Obese and Those Struggling to Reach Their Dreams.

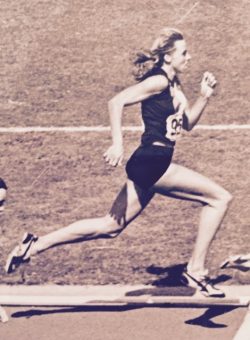

In Australia, I was a star runner. My interest in athletics followed the example of my father, Ivan Baumgartner, a talented professional player in Australian Rules football, the nation’s leading sport.

Mine was an especially youthful career. At the age of 11, I won two Victoria state championships. At 14, I became Australia’s leading track athlete, breaking one national record after another for 400 and 800 meters. At 17, I won a gold medal at the quadrennial Pacific Conference Games, in which five nations, including the U.S.A., competed in Christchurch, New Zealand. Although I gained a place in the 1980 Moscow Olympic Games, political pressure, stemming from the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan, forced me to withdraw.

My disappointment at missing the Olympics that year was tempered by the prospect of a future Olympic spot. It seemed a sure thing to me and to the mass media. They called me an “exciting talent,” tagged me with appellations like, “The Golden Girl of Australian Athletics” — I had long, blonde hair — and glamorized me into a superstar. I appeared in commercials for a vitamin maker and a French sporting goods company, and Nike gave me a monthly sponsorship. The ballyhoo from TV, newspapers, and magazines grew so frenzied that it led grown men to camp outside my house, seeking my autograph.

Although track and field sports were hugely popular in Australia, for its media to give that much attention to a runner and to any sports amateur was highly unusual at that time. I guess I was their pin-up girl. They painted a picture of an attractive and supremely confident young sportswoman with an elevated ego. Yet the real Michelle was a confused girl with minimal self-esteem, unable to bear the incessant pressure and stress.

* * * * * * * *

When I turned 18, my five-foot, ten-inch figure changed rapidly from a lanky 132 pounds (59 kg) to a stronger and more muscular 144 pounds (65 kg). My coaches expressed concern: Was I putting on too much weight? Would this affect the promise of an international running career? The changes worried me too. Like many female athletes, I associated thinness with fitness and muscles with masculinity.

For the first time in my life, I went on a diet. Suddenly, food became a controlled substance, and I could no longer eat as I had always eaten: whatever and as much as I wanted. The diet was rigid. My coaches did not teach me which foods were necessary for health — only which ones were low in calories, and I had to count every calorie.

In cutting calories, I went far beyond the prescribed diet. I was obsessed with my body image. I feared that if I were not rail-thin, I would be a failure and condemned. “I need to be thin to be successful and loved,” my thinking went. “I must starve to maintain my figure.”

Breakfast typically consisted of an apple; lunch, a chicken broth; and dinner, a bird-sized portion of steamed vegetables or a green salad without any dressing and occasionally a little portion of broiled chicken breast or fish. My parents and coaches insisted that I eat more. I did. Then I retreated to the bathroom, thrust my fingers into my throat, and disgorged.

At that time, my mother and father were going through a bitter divorce. My father, who had been my greatest fan and the most enthusiastic supporter of my athletic career, went to live with another woman. She wanted no part of me.

Self-belittling thoughts consumed me: “I am unlovable…. I am not good enough…. I must have been a bad person to be so rejected…. I am unworthy…. I am unattractive.” And so on.

My athletic career began to crumble, in large part because of my food mania and my mental state. But in addition, I lost my passion, even my fondness, for the sport I had loved. I used to run for the joy and satisfaction it brought both my dad and me. Now he was gone and I felt bitter and angry with him. I thought, “Why bother to succeed when no one would care?”

As I shed more and more pounds, I began to feel less miserable. For one thing, I started to attract attention when some coaches saw my skinny frame as advantageous. Then too, I felt more feminine than when I had a more muscular, “masculine” frame. Moreover, inasmuch as all the successful athletes I knew seemed to me to be happy and have extremely low body fat, I thought that I too would find success and happiness that way.

Such thoughts distorted my view of reality and myself. When I gazed in the mirror, I did not see a sick, emaciated girl; I saw a model athlete: fit, vibrant, and feminine.

People said I looked ill and too thin. I ignored them. A skinny body, I thought, ensured athletic success. At least I felt more successful, and more feminine too. Part of my motivation was a belief that my success would bring my father back home. All of those notions were delusions.

In reality, my obsession to acquire what I imagined to be a perfect body would put the brakes on my athletic career and cause me further ailments in the years that followed. I was weak and mentally disabled, and my body was failing me.

I had lost sixteen pounds (7 kg), dropping my weight down to 128 pounds (58 kg) at the age of 19. But I was maturing into a woman, no longer the lanky teenager. So much of what I lost was muscle, not fat.

A doctor told my coach and parents that I was gravely ill and must be removed from the track until well. In an intervention, my family and coach warned me that if I continued on the same path, they would never allow me to run again.

So at age 20, I gave up running. I pursued college studies, directed girls’ sports for a private school, and tried my hand at business. Any chance to compete in either the 1984 or 1988 Olympic Games disappeared. But more than the Olympics, I had lost my health, my good looks, and my self-esteem. I realized that if I was ever to recover, it was up to me.

* * * * * * * *

Ultimately, I learned to love my body — fit and strong, yet feminine. But the change did not come smoothly.

Although I stopped starving myself, I struggled with dysfunctional eating for a few more years. I ate emotionally. To soothe myself when upset or depressed, I would overeat till it hurt. Then I would go out and frantically exercise to try to burn off the excess calories. I hated myself for overeating and sometimes reverted to casting up my food, a common symptom of the illness bulimia.

The real turning point came in 1989 when two athletes referred me to George Krupinski, a Melbourne Hypnotherapist and Performance Coach, who had greatly helped them. The pair was, by the way, rowing partners and Olympic medalists. One of them was a long-term boyfriend of mine, who felt certain that my problems were basically mental.

The real turning point came in 1989 when two athletes referred me to George Krupinski, a Melbourne Hypnotherapist and Performance Coach, who had greatly helped them. The pair was, by the way, rowing partners and Olympic medalists. One of them was a long-term boyfriend of mine, who felt certain that my problems were basically mental.

Krupinski treated me for a few months, finding the causes of many of my troubles buried in my subconscious mind. A form of hypnotherapy that he called guided imagery summoned forth the negative thoughts — hitherto largely hidden in my subconscious mind— that had caused my self-destructive behavior. Positive, productive thoughts replaced them, setting me on the road to health. As a valuable dividend in the meantime, the treatment enabled me to rebuild my relationship with my father.

In essence, these were my old thoughts — followed by my new ones:

- I am unlovable — I am well loved and nurtured.

- I am not good enough — I am great the way I am and I only getting better and healthier.

- I am not worthy — I am worthy of love and respect.

- I am unattractive — I love my toned, lean and muscular body.

- I must starve to maintain my figure — I must nourish my body with healthy, nutrient-rich foods.

- I need to be thin to be successful — I need to be strong, adaptable, and smart to be successful.

- I must have been a bad person to be so rejected — I am not responsible for my parents’ divorce, but I am responsible for my actions and thoughts.

In my mid-twenties, I made a brief comeback and represented my country in the 1990 Commonwealth Games in Auckland, New Zealand. Although inexperienced in distance running — my championships and favored events had been in 400- and 800-meter runs — I entered the 1,500-meter event at my coach’s insistence and against my better judgment, respectively making it to the final. But the next year in Adelaide, at the Grand Series competition, pitting Australia’s leading athletes, I scored a solid victory in the 800-meter event and thereby placed an Olympic qualifying time for the forthcoming Olympics, to be held in Barcelona, Spain, in 1992.

Early in 1992, however, my Achilles’ tendon ruptured, and I underwent surgery. Nonetheless, the famous British sprinter, Linford Christie, and his coach, Ron Roddan, approached me with an invitation to train with them in England. I went there, together with my American fiancé, but found that I could not run without intense pain. Roddan, though a gifted coach, could not help a wounded athlete.My athletic career was prematurely over, I soon moved to the U.S.A. and settled in northern California to start my new life with my husband-to-be.

* * * * * * * *

How did helping people who suffer from obesity become my main calling, when the crisis I had faced was starvation? I have been asked that question, and my answer is threefold.

- I’m concerned that obesity has reached epidemic proportions in Western society and nations adopting its ways. In the U.S.A., more than 2 in 3 adults and 1 in 3 children are considered to be overweight or obese, according to the official Centers for Disease Control. Being a mother of three and seeing the disorder afflict children has particularly touched my heart. I feel that I can make a difference.

- For years I watched one of my siblings struggle with being overweight, fed by social and personal pressures. She would swing between gaining excessive weight and plummeting pounds as she tried and failed one painful diet after another before getting her life and weight under control. I knew then that dieting was not a good solution.

- I realized that our two ailments, though superficially opposite, had much in common. Whether you are overeating and obese or intentionally under-eating and emaciated, you are suffering from a dangerous eating disorder. My primary disease had been anorexia nervosa and bulimia. Like obesity, it thrives on distorted thoughts, beliefs, and self-images. Replacing them with doses of the right kind of thinking is the main treatment for anorexia and bulimia. The same is almost always true for obesity.

A thought may seem weightless and unsubstantial. Yet it has power, as you read throughout this book. And it is the genesis of monumental change, good or bad.

How sad and futile it is for a person with a negative self-image to look in the mirror and think, “I’m fat. I’m ugly. I have no self-control. I’ll never lose weight or be happy.” Such defeatist thoughts cause more of the same — unhealthy habits and unhappiness or worse.

Happier and more constructive outcomes are likely to result from positive thoughts. That person at the mirror would be better served by an attitude of this sort: “I love my body and will do whatever is necessary to nourish and care for it. I’ll get better and better. Hurray for me!”

Such thinking contains the key to success.